The Role of Energy in German Agriculture

By Meggie I. Foster, Farm World Assistant Editor |

| Day 1 - Berlin |

|

Even after a long nine-hour flight, I couldn't wait to get on German soil to immerse myself in the culture, and especially the agriculture industry and its connection to bioenergy programs and solutions during the first day of my seven-day fact-finding mission on "The Role of Green Energy in German Agriculture," sponsored by the German Federal Foreign Office, thorough its Embassies in Washington, D.C. and Ottawa. Additionally, I was looking forward to discussing some of the activities of Midwest bioenergy officials in respect to energy solutions, as well as the controversial climate change legislation in Washington, D.C.

I must admit, I had some preconceived notions about Germany prior to my landing, particularly the food and the people. And frankly I was under the impression that the United States was far more advanced in the bioenergy sector than at least a few countries in the European Union (EU). Boy, was I wrong!

During our first visit to the German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection, Dr. Hans-Jurgen Froese who serves as the deputy director of the agency told us, "it should matter that the U.S. pay attention to what we are doing because of the EU sustainability ordinance."

Renewable Energy Act

Froese and his collegues at the Ministry went on to describe Germany's Renewable Energy Act (EEG) and the implementation of energy and climate-protection goals with a specific focus on EU agricultural policy and sustainability ordinance. Adopted in 1991, EEG provides written incentives for commercial operators and farmers interested in the production of regenerative power, as well as provided energy recommendations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

He mentioned that the key reasons for Germany's focus on a renewable energy strategy are environmental and climate protection issues, food security, conflicting demands from other countries and the security of the energy supply. In Germany, nearly 70 percent of the energy supply is received from outside the country lines, forcing the area to be highly dependent on its political connections in neighboring countries such as Russia and the Ukraine.

The target for the EU is to nearly double the electric share from heat and power to 25 percent renewable resources by 2020 and increase the share of renewable energy in power regeneration to at least 30 percent by 2020. Currently, renewable energy makes up for only 7 percent of primary energy consumption in the EU. In 2008, Germany landed ahead of the curve with nearly 15 percent shared in renewable energies in the gross power consumption, tripling its number in the last three decades, according to Froese. Wind makes up for 44 percent, water power 23 percent, and around 29 percent of the power is generated from biomass. And while biomass in the United States, especially the Midwest, is defined as corn residue, wood and paper waste; in Germany, biomass primarily involves rapeseed, wheat residue, grass and pasturelands.

Froese also discussed Germany's climate protection goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 35 percent in the next 10 years by utilizing the bioliquids and biogas sectors.

According to Froese, this all plays into the EU Directive on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources, in which Germany has played a strong role.

"The law said that you have to meet the criteria by 2013, reaching 35 percent usage of bioenergy sources versus fossil fuels," he explained. "Germany has been quite aggressive in this area at 18 percent."

This directive is being implemented in two separate ordinances including biofuels and power generation, with a central focus on sustainability. One of the most interesting points of my meetings today was the fact that the EU and Germany are focused primarily on energy sustainability, rather than energy independence. In addition, just as an observation - climate change legislation seems to be much more favorable in the EU among the farming community than in the Midwest.

Opportunities for German farmers

With over 82 million people residing in Germany, there is an increasing energy demand and a growing opportunity for German farmers to find an additional outlet for income through renewable biomass production, according to Christian Virks, at the Ministry office. Additionally, biomass production offers a greater opportunity to secure a climate protection strategy, secure the energy supply, new employment in rural regions and further technological advancements.

More specifically in the price arena benefits of renewable energy production, plant operators can receive up to 11.67 cents per 150 kilowatt hour for producing energy or they can directly market their "power" to grid operators on a month-to-month basis.

Farmers are paid for energy production dependent on the size, type of energy resource and year that they started.

Similarily to the United States, the German government is highly funding the development of second generation biofuels from cellulosic ethanol due to its high potential to further reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It also provides an additional opportunity for automotive manufacturers. In the United States, all vehicles are capable of running on E-10, or 10 percent ethanol and 90 percent gasoline. In Germany, currently, there is a law that limits the blending rate to 5 percent.

Another interesting point made during the discussion is the fact that all German consumers contribute 12 percent to the renewable energy sector (including wind, solar, water and biomass) through a purchase agreement in his/her energy agreement.

"Consumers pay for renewable energy here in Germany, it helps ensure the financial burden is the same for everyone," said Janet Leisker, a policy officer at the Ministry.

In addition to the Ministry office, we also visited and met with other government officials specializing in the area of solar energy production during a delicious lunch at the Einstein Café in beautiful downtown Berlin.

From there, we traveled to Clearingstelle EEG, a firm that serves as mediator for legal issues in renewable energy.

Berlin architecture

Also, we enjoyed a brief tour of sustainable architecture in Berlin with a few stops of key historical areas of Berlin including the site of the deconstructed Berlin Wall, the historic Brandeburg Bridge, the Energie Forum, a office building built according to strict sustainable guidelines including solar panels and hydro power; Topography of Terror, the former headquarters of the Nazi regime and a current location being transformed into a memoral; the Holocaust Memorial, a unique abstract display of 2,011 concrete blocks of different sizes and heights laid out separately to signify the 6 million deaths during the Holocaust; Reichstag, built in 1894 and home to the German parliament. An interesting land structure, Reichstag, modernized in 1999, uses a naturally ventilated system through glass and solar panels on the glass dome atop the structure and features two biofuel plants, and two indoor water storage thermasystems one heated in the summer to use as winter heat and the other cooled in the winter to provide a cool environment in the summer.

And finally, our evening brought us to a fine dining experience at a restaurant called Faustus, where we were able to mingle with two media representatives, Ms. Catrin Hahn and Ms. Anke Sefling, from a popular German agriculture magazine known as Neue Landwirtschaft or "New Agriculture." A very interesting discussion prevailed on issues facing German farmers and U.S. farmers, how they are similar and how they are very different. Tomorrow, we transfer to the historic city of Leipzig in north east Germany.

For more basic information on the journey and how I was selected to participate please refer to the preview article in last week's (Sept. 30) Farm World.

Respectfully submitted,

Meggie Foster,

Assistant Editor

Oct. 5, 2009

|

|

|

|

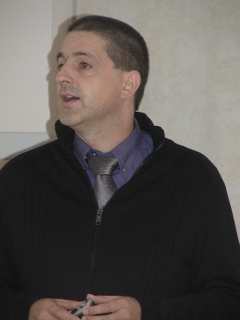

| Dr. Hans-Jurgen Froese |

Dr. Martin Winkler at Clearingstelle EEG in Berlin discussing the EU's energy sustainability ordinance. |

Open German elevator in Federal Ministry office that is constantly moving, reminiscent of a dumb-waiter. On board is our guide and InWent coordinator Eva Daub. |

|

|

|

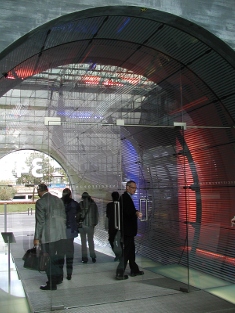

| Energie Forum in Berlin, part of our sustainable architecture tour. |

Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection officers Janet Leisker, Christian Virks, Dr. Hans-Jurgen Froese and Leisker's translator engaged in biomass discussion on Oct. 5 in Berlin. |

Our group enjoying a lunch at Café Einstein with German political officers. |

|

|

|

| Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection office building. |

Energie Forum, energy sustainability walkway including water heating element below. |

|

|

|

| Distant view of Checkpoint Charlie, a potent symbol of the Cold War, that served as the main gateway for the Allies, other non-Germans and diplomats between the two Berlins from 1961 to 1990. |

Historic structure with soccer field in downtown Berlin. |

|

| Day 2 - Potsdam, Ludwigsfelde and Leipzig |

|

Day two of this seven-day fact-finding tour in Germany brought not only a very early morning in Berlin, but a late, yet memorable evening in the eastern city of Leipzig.

We began the morning in Potsdam, the capital and crown jewel of the state of Brandenburg. Rich with German political history, Potsdam was once home to Frederick the Great, who served as the visionary for many of the famous gilded palaces and parks in the city.

While the surroundings in the city certainly captured our attention and photo lenses from the bus, we focused much of the day at the Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering (ATB). By combining scientific and engineering findings, especially in biotechnology and information technology, ATB aims to ensure that newly developed processes and technical solutions are profitable for both manufacturers and farmers, while remaining environmentally-friendly and sustainable. Specific research in the field of agricultural engineering includes renewable resources, biomass for energy and bioplastics; as well as food quality and safety.

"We serve as the experimental farm of the Agricultural University of Berlin," said Dr. Reiner Brunsch, of the Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering (ATB). "Our task is to create the scientific basis for new technology for sustainable land use purpose as well as develop technical solutions or prototypes."

During this visit, we were also able to view some of the Institute's test sites on biomass production for energy use including a willow and popular plot. According, to the Institute's Public Relations Specialist Helene Foltan, they have found that willow and popular is quite suitable to grow for biomass production because they are fast-growing woods that can grow well on marginal soils.

Since they are two- to five-year crops (corn and soybeans are annual crops), Foltan said that the labor needed to produce these trees is relatively low, however, the cost to remove and harvest the trees is high due to the use of expensive machinery.

Biomass research initiatives

Clearly, one of the key areas of focus at the Institute is the research of biomass and how it can produce biogas for energy purposes.

According to young researcher Jan Mumme, the goal is to research new sources of biomass that provide a high fiber content for the highest yield, as well as invent new processing technology to produce biogas from such organic materials as corn silage. Additionally, Mumme discussed the combined energy potential of biomethane and biochar.

"Biomethane is a highly versatile energy source, whereas biochar can be applied to the soil as a fertilizer and be used for long-term carbon storage. Biochar, a charcoal material created through the decomposition of biomass during heating, is known to be stable in the soil for nearly 1,000 years," Mumme explained.

With so many potential sources of biomass resources available for research from cattle and hog manure to wood waste and fruit pulp, it seems as if the Institute has their work cut out for them.

"Whatever contains carbon, we can test - because it has a certain amount of energy potential," said Foltan.

Also, our group had the interesting opportunity to tour a hemp research and small production facility at the Institute. Acccording to Foltan, hemp production was prohibited in Germany and the majority of the European Union until 1996.

"Since then, there exists a tremendous lack of knowledge on how to produce and harvest hemp as a raw material," said Dr. Peter Schmuck, a professor at the University of Management and Communication in Potsdam. Currently, the Institute is researching new ways to utilize dry hemp fibers out of the straw hemp plant and produce an insulation type material, similar to what we would consider particle board.

Bioenergy Region in Germany

Next we traveled to the city of Ludwigsfelde, located just adjacent to the southern area of Berlin. Ludwigsfelde is best known as a "Bioenergy Region" in Germany, granted this status by the German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection. Objectives in this region as laid out by area planners focuses on becoming a more energy self-sufficient community beginning with raw material (biomass) production through the conditioning to conversion and utilization of bioenergy. Currently nearly 25 areas in Germany have been named a "Bioenergy Region," through clear outlined objectives designed to become more aware of climate change protection and energy sustainability.

"There has been a lot of discussion in this area on the global temperature change that indicates a 1 degree increase in global temperature, this is what has sparked much of our climate change concern," said Professor Kaupen Johanns.

According to Johanns, the world can only afford a 2 degree maximum increase and because of burning coal, "we expect a 4 to 6 degree increase in the next 150-200 years. So currently, we do not have a very good energy protocol to stay around 2 degrees, so we wanted to come up with a plan for our area in hopes that it will catch on."

Later on in the afternoon, we meet with two area farmers who discussed the poor crop harvest suffered during the last 3 years. One large-scale organic farmer, Erhard Thale, who farms over 2,000 acres of rye, peas, corn and grass with his family, is considering switching to energy crop production for its potential price advantage.

"We have had three long years of losing money, with the soil quality here we get low yields and our subsidies are decreasing too," said Thale. "It may be time to consider a new alternative, I'm looking at all my options."

Leipzig -trade and music mecca

Quite a busy day, we missed our tour of the wood pellet production facility and proceeded to our hotel transfer in Leipzig. What a beautiful and historic city! Leipzig once served as the trade mecca of Europe, as well as home to many famous classical composers including, Sebastian Bach, Schumann, Wagner, Mendelssohn and to Goethe. Leipzig, also is well known as the "City of Heroes," for its role in the 1989 democratic revolution and peace riots against the communist regime in May of that year. Just arriving in Leipzig, we took a scenic city tour in the evening and enjoyed a lovely German dinner in the historic downtown scene where Bach's music once echoed down the cobble stone streets of the city. Unfortunately, a evening rain dampened our slightly misguided walk back to our hotel, but the sights and the sounds of Leipzig were well worth our rain-soaked jackets!

Respectfully submitted,

Meggie Foster,

Assistant Editor

Oct. 6, 2009

|

|

|

|

| Willow (left) and poplar trees (right) |

Hemp plant |

Biogas testing area at the Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering. |

|

|

|

| Board material made from processed hemp. |

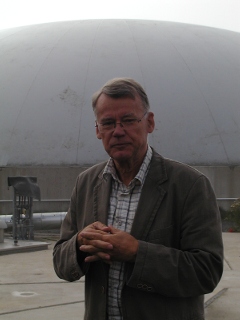

Dr. Reiner Brunsch, scientific director at the Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering (ATB). |

Organic farmer from Germany Erhard Thale discussing his situation and consideration of energy crops as alternative income source. |

|

|

|

| Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering Researcher Jan Mumme explaing the production of biochar and biomethane in a combined energy system. |

Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering Public Relations Specialist Helene Foltan explaining willow and poplar production for biomass research efforts. |

Discussion on Bioenergy Region of Ludwigsfelde at future location for biomass production at a former toxic waste area. |

|

| Day 3 - Leipzig |

|

During day 3 of this German green energy mission, we visited two sites in Leipzig focused on the research and production of biogas, Verbio Biofuel and Technology and the German Research Centre. Not a single day or possibly even hour has passed since we've been traveling in this beautiful countryside, that I haven't absorbed a new digestion of information and culture that truly defines the country of Germany.

Starting out the morning - Verbio Biofuel, opened in 2001, certainly made for an interesting visit as it is the first large-scale facility in Germany to launch a biorefinery, where they will produce biogas, biofertilizer and bioethanol in the same location. The operation has already begun to produce bioethanol and production of biogas will begin in December of 2009. The biorefinery will generate a total of 100,000 metric tons of bioethanol, 450,000 metric tons of biodiesel and 40-80 megawatts of biogas (natural gas). The Germans claim that biogas is one of the most high yielding, lowest costing bioenergy solutions and hooks into the country's existing natural gas infrastructure, which unfortunately the United States, at least the Midwest is not blessed to have.

"This is the newest innovation in the energy area, where we will combine bioethanol, biogas and biofertilizer production into one facility," said Business Line Manager Oliver Ludtke. "Using grain and straw to produce fuel (sold to filling stations as E-85 and sold to refiners for use in E-10), using crop residues to generate biofertilizer and the cellulosic structure to produce biogas, this is not just a vision but a reality."

We are optimizing the entire biofuel value chain from farmers (about 4,000 farmers from a 50-75 kilometer range) to the consumer and back to the farmers, as they have the opportunity to purchase or receive back the biofertilizer for their fields," he added, further explaining the facilities closed loop self-sustaining energy system.

The key target of Verbio is to provide the highest energy output per hector, the highest greenhouse gas savings, while remaining competitive and minimizing the global warming effects of CO2 from burning fuels. Another goal of the company outlined by Ludtke, is to license the biorefinery technology and market it worldwide.

"Our statement is that we produce third generation biofuels with the cost of first generation plus the CO2 reduction of second generation," commented Ludtke.

In the United States and particularly the Midwest, ethanol and biodiesel plants utilizing corn and soybeans commonly dot the map, and cellulosic ethanol has remained on the verge of development in pilot stages and small-scale production.

Next we toured the German Biomass Research Centre (DBFZ), where scientists are looking for methods that facilitate an effective and sustained use of solid, liquid and gaseous bioenergy sources. Funded entirely by the federal German government, DBFZ includes six research departments: bioenergy system policy, biogas laboratory and technology, biogas gasification production, biofuels and international affairs.

Today was another long day of tours and meetings, but the rich German food is certainly the fuel that keeps our group moving forward. My lunch at the historic Auerbauch Keller in Leipzig, was titled Farmers' Saxony Pan, a gratin dish with sauerkraut, potatoes and pork neck meat cooked to the utmost tenderness. Clearly, this traditional German fare was well worth the experience for my tastebuds, alone.

Tomorrow, we will tour an agricultural training center for pilot energy plants and the Institute for Wind Energy and Energy Systems Technology.

Respectfully submitted,

Meggie Foster,

Assistant Editor

Oct. 7, 2009

|

|

|

|

| A biomass combustion testing chamber at the German Biomass Research Centre used to research the advantages and disadvantages of blending materials such as straw and wood, for instance. |

Still under construction, Verbio hopes to begin production of biogas in the containers seen here in December of 2009. |

Bioethanol containers at Verbio Biofuels in Leipzig, Germany. |

|

|

|

|

A field of solar panels outside of Leipzig. |

With 8 journalists and two radio broadcasters from both the United States and Canada, we like to have a lot fun during our travels as well as take up the opportunity to learn about each other's publications. |

|

|

| Professor Kaltschmitt at the German Biomass Research Centre explained the benefits of biogas production on Oct. 6. |

Verbio Biofuels Business Line Manager Oliver Ludtke discussing the new technology launched in Leipzig to produce biogas, bioethanol and biofertilizer in a singular biorefinery unit. |

|

| Day 4 - Bad Hersfeld and Kassel |

|

This morning we had the joy of encountering areas of beautiful countryside in rural western Germany as we traveled from Kassel to Bad Hersfeld in Germany to tour Gut Eichhof, an agricultural training center and research farm. I must admit, I felt as if I was traveling through western Colorado, with its small towns nestled into country mountainsides and valleys similar to Telluride. However, what was different is that the homes and farms in this area of the world are several hundred years old, some dating back to the 13th century. In the fact, the main office of Gut Eichhof in the state of Hessen is referred to as the "castle" and was built in 1251 as a monastery; once rumored to have encountered a visit from Martin Luther.

But enough about the history and landscape of this charming area, although clearly as a Midwesterner, it has captured my attention and appreciation. As I mentioned, today we toured Gut Eichhof, which not only serves as training school for young pupils interested in production agriculture, but also as a consulting organization for farmers and gardeners, according to Andreas Sandhager, director of the school in Hessen.

Many exciting areas of research are being developed in Hessen, including a tremendous amount of work with renewable energy. Specific studies include biogas, plants for cofermentation and ways of utilizing biogas.

"It is becoming more and more important to give farmers an opportunity to earn more money than say dairy production alone," said Klaus Wagner, of the Hessen school. According to Wagner, every state in Germany has their own agricultural training center, which offers research and the opportunity for students to enroll in 1-2 day courses and up to 3 years worth of farm studies and apprenticeships.

In fact, Hessen is working with the Fraunhofer institution, one of the largest research and development firms in the country focusing on bioenergy systems including wind, solar, hydropower and biogas.

"We don't develop components, what we do is work to integrate renewables into the energy supply," said Dr. Bernd Krautkremer, an engineer at Fraunhofer.

Krautkremer added that the biggest problem holding Germany back in this area is that there are only a few players in the power supply chain and "in the beginning they saw renewable energy as an annoyance, a negative load and they only saw high costs for them. Tomorrow (in the future), we expect some new operators to come on board, where we can tailor the technology to fit their needs. For instance, a mixture of wind, wood, photovaltaic (solar) and bioenergy (biogas)."

What we want to do is show what can be delivered from the biogas sector to the grid, we care about is power, voltage quality and everything you need for power to be reliable," he added.

Krautkremer said this is just one step to break through the system. Of course, cost is also a concern - 'who will pay for all this.' They do not know the answer to that question, yet.

Wagner hopes that many farmers will soon come on board to build small biogas plants and sell their leftover power to the grid.

German dairy industry

"You need good quality silage (and manure) to produce quality biogas, that's why dairy producers are the best because they are the ones who understand how to grow silage," he explained, adding that currently German (and EU) dairy farmers are in an economic crisis crunch with a milk price of 21 Euro cents per liter and a cost of production at 33 Euros cents per liter. Breakeven for German producers is around 40 Euro cents per liter of milk, he added.

Wagner cited the reason for the high milk price is a rate of 104 percent overproduction of milk.

"We see it as very beneficial for small farmers (the average dairy herd in Germany is 50 cows) to build these (biogas) units, rather than large corporations," he stated. "We say 'pay attention farmers, don't let these guys take over the market,' let's share the profit, instead of corporations trying to take it all."

Krautkremer added that German farmers can earn up to 21 Euro cents per kilowatt hour from producing and selling on-farm energy utilizing corn silage and cattle manure, for instance.

"Milk production and energy production belongs together- it's a sort of synergy," said Wagner. "Farmers can earn extra money from the energy of their cows that is otherwise considered waste."

Currently, 4,000 farmers in Germany have opened a biogas operation on their farms, primarily used to generate electricity.

Tomorrow, I am very exited about traveling to the first biovillage of Germany powered majorly with renewable energy in Juhnde from nearby farmer. Reminds me of the development of Indiana's own BioTown in Reynolds, Ind. More to come in tomorrow's blog! Tune in!

Respectfully submitted,

Meggie Foster,

Assistant Editor

Oct. 8, 2009

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Bernd Krautkremer teaching us about the cooperative work being done in renewable energies at Gut Eschhof, an agricultural training and research facility in Bad Hershfeld and Fraunhofer, IWES, an applications-oriented research group in the field of electrical engineering in Kassel. |

Klaus Wagner describing the harvesting cycle of miscanthus used as a biomass resource for a biogas heating chamber. |

Gut Eschhof in the state of Hessen, Germany is home to a historic structure known in the area as the "castle," built in 1251 as a monastery and today operated as an agricultural training center for farmers and gardeners. |

|

|

|

| Historic townhouses in downtown Kassel. |

Vista of church tower in the city of Kassel. |

Another view of the original "castle" built in 1251 in Bad Hersfeld, Hessen, Germany. |

|

|

|

| A scenic view of only a small areas of the research farmground at the Hessen center. |

The farm's robotic milking system was added in 2003 and eliminates the need for a traditional parlor as the cows decide when and how often they would like to be milked out. |

We gathered around closely to learn about the German dairy industry and the farm's robotic milking system. |

|

|

|

| My entrée at lunch, boiled beef with baked cabbage wrapped around it, as well as boiled potatoes. |

Our group of journalists learning about popular and miscanthus production used to provide biomass for a biogas combustion unit. This combustion unit generates heat for the Gut Eschhof farm's greenhouses and meeting room facilities. |

Many of us were happy to capture some German cows on film at the Gut Eschhof farm in Hessen. The farm operates a 100 sow swine operation, as well as a 120-cow dairy that uses a robotic milking system. |

|

|

| Wood chips used to as energy source for the farm's biogas unit. |

Biogas chamber that generates electricity from cattle manure and corn silage. |

|

| Day 5 - Juhnde, Hardesgen and Kassel |

|

It's hard to believe today was our last full day in Germany! As my first official visit to Europe, I must admit I am quite impressed with the country of Germany. From the foods to the kindness of the people and the innovations in bioenergy, this tour far exceeded my expectations. Another surprising aspect to this adventure was the connections and new friendships I made with my 10 fellow journalists. What a great group of individuals from all parts of the United States and even Canada. I am very much looking forward to keeping in touch with many of my new friends.

So today, we visited the bioenergy village a Juhnde located in western Germany. While still a novel concept in Germany, Juhnde has piloted the country's first official community powered nearly 75 percent through renewable energies. Currently, Juhnde generates electricity and heat through its independently produced supply of biomass from neighboring dairy and grain farms. What an impressive accomplishment as the village has already exceeded the European Unions bioenergy goals set for 2050. This of course reminded me of the Indiana State Department of Agriculture's own pilot community known as BioTown, USA in Reynolds, Ind. In 2005, the concept of BioTown, USA was launched to generate its electricity through renewable resources from neighboring farms utilizing hog manure and corn stover. In response to my visit to Juhnde, I am looking forward to connecting with officials in BioTown to get an update on its progress and their work with Juhnde.

In addition to visiting the biogas production facility that generates heat and electricity for the village, we visited with a Juhnde dairy farmer who explained his work in providing a constant supply of cattle manure to produce biogas.

(More on Juhnde later)

After a delicious golash soup lunch, we visited a biogas production plant in Hardesgen, known as E-on Mitte AG. Referred to as a biogas plant of the third generation, E-on Mitte explains that the first generation is operated by farmers, second generation is operated by commercial heat and power plants larger than 600 kilwowatts and the third generation biogas is located in rural areas provides an energy yield of 50 percent heat, 50 percent electricity.

43 farms in the area provide the corn sillage and cattle manure to generate power for this facility that "could" power homes for nearly 10,000 people.

However, E-on Mitte is unique in that the plant is not in control of distributing the power. How it works is that E-on Mitte provides the biogas for cogeneration units that are located in schools, hospitals and industrial operations needing larger supplies of energy.

Well I need to get on my plane for Charlotte, N.C. here shortly. In one sense, I am sad to leave Germany, but mostly I'm looking forward to getting back on U.S. soil, reuniting with my family and sharing all of the many insights into German agriculture and bioenergy from this mission. I have learned more about German bioenergy policy, research and practical applications than I could of dreamed of. And I hope that through my writing I am able to spark new ideas in the minds of Midwest farmers and how they can play a bigger role in providing a renewable energy resource and receiving an initiative for doing so.

Note: Meggie is catching a very early flight from Frankfort this morning - so more will be added to her blog this weekend.

Respectfully submitted,

Meggie Foster,

Assistant Editor

Oct. 9, 2009

|

|

|

|

| International School of Farming Director Axel Unger explains that at any given time 40 students ranging in grades from elementary school to vocational school are visiting the School to learn about agriculture and participate in farm world such as milking, feeding and processing products such as cheese. |

Plant manager Berud Kohler of E. on Mitte AG discusses the power generation cycle of his facility's biogas plant that can supply energy needs for nearly 10,000 people. |

Gerd Paffenholz volunteers as a tour guide for the village of Juhnde, Germany in Lower Saxony. Juhnde is a community of 750 residents that produces 75 percent of their heat and electricity by means of renewable biomass. |

|

|

|

| The U.S. and Canadian delegation stand atop stairs of one of the 4,100 cubic meter bunkers that holds corn sillage at E. on Mitte AG, a biogas plant of the third generation in Hardesgen. |

Meggie Foster, of Farm World standing in front of wood chips and a solar panel in Juhnde. |

Our delegation met with Juhnde dairy farmer Karsten Harrihausen and his wife who supply cattle manure (from 130 cows) for the anaerobic digestion unit that produces biogas, contributing to 75 percent of Juhnde's energy needs. |

|

|

|

| One of the 80 sheep at the International School of Farming munches on some fresh cut greens. |

Corn sillage from neighboring farms that is used to supply the anaerobic digestion plant in the village of Juhnde. |

Dairy cattle manure being loaded into a collection chamber for eventual biogas production. |

|

| Juhnde dairy farmer Karsten Harrihausen said that he can survive in the dairy industry, despite low prices, because he receives an incentive for providing feedstocks for town's digester unit. Here he shows our group his 18-cow milking parlor built in 1993. |

|

|